Building a Gameboy Emulator in Rust: Step-by-Step Guide (Part 1: CPU)

Creating a Gameboy emulator in Rust is a cool project that offers a hands on way to learn about computer architecture, emulation, and Rust’s systems programming. In this blog series, we’ll walk through building an emulator from scratch, focusing on the various components that make it work.

There are many amazing resources to learn about the Gameboy architecture, such as gbdev and this online talk. For the first part of the blog, we will introduce and implement the CPU architecture. The full implementation will be in the Git repo:

This tutorial will cover parts of src/cpu.rs and src/memory.rs.

Gameboy CPU Architecture

The CPU is the core of any emulator. In the Game Boy, this CPU is based on an Intel 8080-inspired architecture.

It’s an 8-bit CPU with a mix of 8-bit and 16-bit instructions, limited addressing space, and a relatively small instruction set. This simplicity makes it easier to implement.

The CPU contains 8-bit registers: A, B, C, D, E, H, L, and F, with the F register used for storing flags like zero, carry, etc. Additionally, the Game Boy includes four 16-bit registers (AF, BC, DE, HL), which are simply the 8-bit registers paired for various operations.

In addition to these registers, the CPU has two crucial 16-bit registers: the Program Counter (PC), which holds the address of the next instruction, and the Stack Pointer (SP), which points to the top of the stack in memory.

We represent the registers inside the struct in the CPU:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

pub struct CPU {

pub a: Byte,

pub b: Byte,

pub c: Byte,

pub d: Byte,

pub e: Byte,

pub h: Byte,

pub l: Byte,

pub f: Byte, // flag

pub sp: Word, // stack pointer

pub pc: Word, // program counter

}

Because there are overlapping possible choices for registers (register A and register AF both contain a: Byte), we create enums to refer to the register we are talking about.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

#[derive(Debug, Clone, Copy, PartialEq, Eq, Hash)]

pub enum Register {

A,

B,

C,

D,

E,

H,

L,

HL,

}

#[derive(Debug, Clone, Copy, PartialEq, Eq, Hash)]

pub enum Register16 {

BC,

DE,

HL,

SP,

AF,

}

Instruction Set

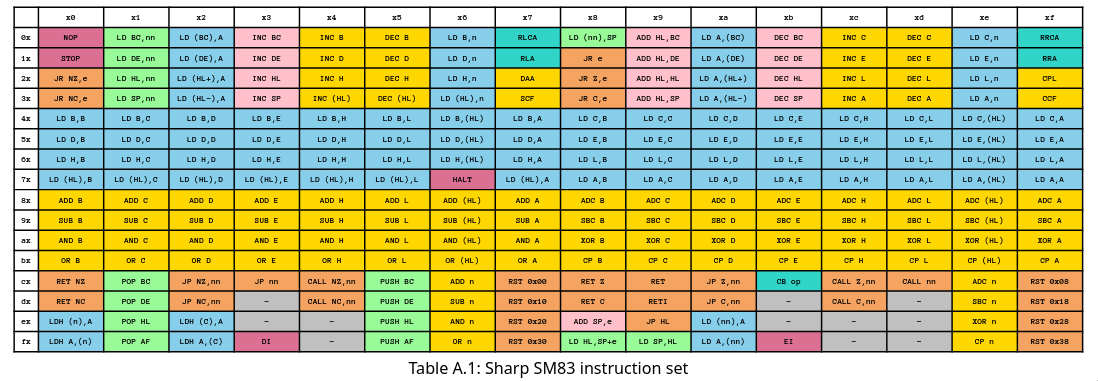

The instruction set is similar to the Intel 8080 processor. It covers data movement, arithmetic and logic operations, branching, and interrupts. The CPU has assembly instruction (opcode) table as such:

For example, this graph says that 0x00 is NOP, 0x10 is STOP.

Because similar operations often differ by only a few bits, for example, LD r1,r2 loads values from r2 to r1, this opcode is represented by the byte 0b01xxxyyy, where xxx yyy specify r1 and r2. For example, 0x41=0b0100_0001 represents LD B,C. Therefore, we represents an opcode with its effective fields.

1

2

3

/// OpCode template with its effective fields

#[derive(Debug, PartialEq, Eq)]

pub struct OpCode(Byte, Byte);

Where the first field is the template, second field is the mask, so LD instruction will have OpCode(0b01000000, 0b11000000), this means that the top 2 bits will be fixed, the other 6 bits will be variable.

For example, . As another example, ADD n adds to the 8-bit A register, the immediate data n, and stores the result back into the A register. The opcode for ADD n is 0b11000110, and it takes the n value from the next value in the instruction.

We then implement the matches method to check if a given opcode matches its pattern. To do so, we simply introduce a few utility functions and type aliases:

1

2

3

4

pub type Byte = u8;

pub type SignedByte = i8;

pub type Address = u16;

pub type Word = u16;

We also introduce some utility functions to convert between bytes and words, and to manipulate bytes and words:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

pub fn bytes2word(lsb: Byte, msb: Byte) -> Word {

(lsb as Word).set_high(msb)

}

pub trait ByteOP {

fn mask(&self, mask: Byte) -> Byte;

fn get_low_nibble(&self) -> Byte;

fn get_high_nibble(&self) -> Byte;

}

impl ByteOP for Byte {

fn mask(&self, mask: Byte) -> Byte {

self & mask

}

fn get_low_nibble(&self) -> Byte {

self & 0xF

}

fn get_high_nibble(&self) -> Byte {

(self & 0xF0) >> 4

}

}

Back to the opcode, we create a matches function that checks if a particualr opcode matches the given byte inside the template:

1

2

3

4

5

6

impl OpCode {

/// Check if the give opcode `code` matches self, considering mask

fn matches(&self, code: Byte) -> bool {

code.mask(self.1) == self.0

}

}

This will allow us to filter out the opcode from the instruction set into its correct execution.

Memory

Before implementing the basic instructions, we need a mimimum viable memory to store the program and data. What happens during execution of a rom is that the CPU copies the instructions from the ROM into the RAM, and then fetches the instruction, decodes it, and executes it. We will implement a simple memory struct that will store the memory structure. Here is a table that shows the memory layout of the Gameboy (from gbdev):

| Start | End | Description | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0000 | 3FFF | 16 KiB ROM bank 00 | From cartridge, usually a fixed bank |

| 4000 | 7FFF | 16 KiB ROM Bank 01–NN | From cartridge, switchable bank via mapper (if any) |

| 8000 | 9FFF | 8 KiB Video RAM (VRAM) | In CGB mode, switchable bank 0/1 |

| A000 | BFFF | 8 KiB External RAM | From cartridge, switchable bank if any |

| C000 | CFFF | 4 KiB Work RAM (WRAM) | |

| D000 | DFFF | 4 KiB Work RAM (WRAM) | In CGB mode, switchable bank 1–7 |

| E000 | FDFF | Echo RAM (mirror of C000–DDFF) | Nintendo says use of this area is prohibited. |

| FE00 | FE9F | Object attribute memory (OAM) | |

| FEA0 | FEFF | Not Usable | Nintendo says use of this area is prohibited. |

| FF00 | FF7F | I/O Registers | |

| FF80 | FFFE | High RAM (HRAM) | |

| FFFF | FFFF | Interrupt Enable register (IE) |

Currently we will only deal with simple cartridge types, so we wont care about switching banks. That corresponds to copying at most 16KB of data into the memory.

1

2

3

4

5

6

pub struct Memory {

memory: [Byte; MEMORY_SIZE],

boot_rom: [Byte; BOOTROM_SIZE],

rom: Vec<Vec<Byte>>,

ram: Vec<Vec<Byte>>,

}

As well as simple read and write functions:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

impl Memory {

pub fn read_byte(&self, address: Address) -> Byte {

self.memory[address as usize]

}

pub fn write_byte(&mut self, address: Address, value: Byte) {

self.memory[address as usize] = value;

}

}

Because the Gameboy has a boot ROM that is executed when the Gameboy is turned on, we need to load the boot ROM into the memory. We will also load the ROM into the memory. We will implement the load_rom function to load the ROM into the memory:

1

2

3

4

5

pub fn load_boot(&mut self, boot_data: Vec<u8>) {

info!("Boot Size {:#04X?}", boot_data.len());

self.boot_rom.copy_from_slice(&boot_data);

self.memory[..BOOTROM_SIZE].copy_from_slice(&self.boot_rom);

}

These boot roms can be found in various websites, and the size is usually 256 bytes. We will also implement the load_rom function to load the ROM into the memory:

1

2

3

pub fn load_cartidge(&mut self, rom_data: Vec<u8>) {

self.memory[BOOTROM_SIZE..ROM_SIZE].copy_from_slice(&self.rom[0][BOOTROM_SIZE..ROM_SIZE]);

}

Now we have a basic memory structure that can store the boot ROM and the ROM. Examples of what the bootrom does can be found here.

Fetch, Decode, Execute

As the final step of the CPU implementation, we will want to fetch the given instruction based on the PC, and execute it.

For ease of debugging, as well as to make the code more readable, we will implement a function that will fetch then decode the instruction into a Instruction enum. For example, the NOP instruction will take in zero arguments, and simply do nothing. The LD_R_R instruction will take in two registers as argued, and load the value from the second register to the first register. To do this, we can use Rust’s enum variant to represent the instruction:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

#[derive(Debug, PartialEq, Eq, Hash)]

#[allow(non_camel_case_types)]

pub enum Instruction {

/// No operation

NOP,

/// Load register (register)

LD_R_R(Register, Register),

/// Load register (immediate)

LD_R_N(Register, Byte),

// more instructions

}

Next, we want to hardcode all the instruction templates into the OpCode struct (as mentioned above). We will then implement a function that will take in the opcode, and return the instruction. To do this, I simply created another Rust impl block for the OpCode struct, and then wrote the different codes as consts:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

impl SizedInstruction {

// ----- opcodes , left is pattern, right is mask -----

const NOP: OpCode = OpCode(0, 0b11111111);

/// LOAD for RR, RHL, HLR,

const LD1: OpCode = OpCode(0b01000000, 0b11000000);

/// LOAD for RN or HL N

const LD2: OpCode = OpCode(0b00000110, 0b11000111);

// more opcodes

}

For example, the NOP instruction will have the exact opcode 0b00000000, and so the mask will be 0b11111111. The LD_R_R instruction will have the opcode 0b01xxxyyy, where xxx and yyy are the registers, and so the code will be 0b01000000, and the mask will be 0b11000000. During the code operation, we will fill in the xxx and yyy with the actual registers.

Finally, we will implement the decode function that will take in the opcode, and return the instruction, this was implemented inside impl SizedInstruction so Self simply refers to SizedInstruction:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

/// Decode the opcode at address into a SizedInstruction

pub fn decode(memory: &Memory, address: Address) -> Option<Self> {

let opcode = memory.read_byte(address);

debug!("Address: {:#04X?}, Opcode: {:#04X?}", address, opcode);

let (instruction, size) = if Self::NOP.matches(opcode) {

(Instruction::NOP, 1)

} else if Self::LD1.matches(opcode) {

let (lr, rr) = Register::get_rr(opcode);

let instruction = match (lr, rr) {

(Register::HL, Register::HL) => Instruction::HALT,

(Register::HL, r) => Instruction::LD_HL_R(r),

(l, Register::HL) => Instruction::LD_R_HL(l),

(l, r) => Instruction::LD_R_R(l, r),

};

(instruction, 1)

}

/// more instructions

else {

return None;

};

Some(Self { instruction, size })

}

The get_rr function is a utility function that will take in the opcode, and return the registers that are being used in the instruction:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

impl Register {

/// Assumes the register values are 0bxxx

pub fn get_r(code: Byte) -> Self {

match code.mask(0b111) {

0 => Self::B,

1 => Self::C,

2 => Self::D,

3 => Self::E,

4 => Self::H,

5 => Self::L,

6 => Self::HL,

7 => Self::A,

c => panic!("Unknown Register {} for code {}", c, code),

}

}

/// Assumes the register values are 0bxxxyyy

pub fn get_rr(code: Byte) -> (Self, Self) {

let lr_code = (code.mask(0b111 << 3) >> 3) as Byte;

let rr_code = code.mask(0b111) as Byte;

(Self::get_r(lr_code), Self::get_r(rr_code))

}

}

Finally, we want to run the instruction. To do this, we simply create an execute function that will take in the instruction, and do whatever the instruction says:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

/// Execute the instruction

pub fn execute(&mut self, memory: &mut Memory) {

let instruction = match SizedInstruction::decode(memory, self.pc) {

Some(ins) => ins,

None => panic!("Could not decode {:#04X?}", memory.read_byte(self.pc)),

};

match instruction.instruction {

Instruction::NOP => {

self.pc += instruction.size;

}

Instruction::LD_R_R(r1, r2) => {

let data = self.get_register(r2);

self.set_register(r1, data);

self.pc += instruction.size;

}

// more instructions

_ => {

panic!("Unknown instruction {:?}", instruction);

}

}

}

For example, the NOP instruction will simply increment the PC by 1, and the LD_R_R instruction will load the value from the second register to the first register, and then increment the PC by 1.

This is the majority grunt work of the CPU implementation, but doing so will also familiarize you with the Gameboy’s instruction set. In the next blogs in the series, we will look into interrupts, as well as the timings of these instructions that we have implemented, and we will add a bit more complexity to the CPU. Follow along with this series by starring the GitHub repo or subscribing for updates!